A cloud chamber is a device for measuring the existence of the intangible. Physicists use them – mapping out the paths that subatomic particles trace through a vapour, studying nuclear reactions and inferring the presence of other particles. There’s something about that last bit I particularly like: inferring the existence of something. Something you can only detect, or believe in, by seeing how it affects something else.

Cloud Chamber (with the capitals) is an improvising group allowing the convergence of several other exotic particles – these being guitarist Barry Cleveland, space-age bass guitarist Michael Manring, cellist Dan Reiter, percussionist Joe Venegoni and Michael Masley, who coaxes sounds out of a more esoteric set of instruments (panpipes, gobek, gobeon and the cymbalom dulcimer). Having come together as part of the Lodge improv evenings in Oakland, California following stints with employers as diverse as Michael Hedges, the Oakland Symphony Orchestra, Ry Cooder and Garbage (plus exploits in journalism and dance theater), Cloud Chamber’s collective past suggests that what they’re likely to condense together will be suckling blissfully on an inspiration of mind and music, devoid of barriers.

More accurately, outside of barriers. When listening to improvised music you’re all too often shoved back on your arse by the force of several musicians protesting their individuality as forcefully as possible, and playing off each other with all the subtlety of dodgem cars. Cloud Chamber, on the other hand, have nothing to do with ego. The fivesome’s music emerges like the interplay of ocean currents; a process of continual organic movement to which the musicians respond as if they’re no more than implements of a guiding force.

And that’s how it needs to be – the compound music that Cloud Chamber produce is as precarious and demanding as improv demands, but to release the life in that music it’s necessary for the musicians to let it play through them. Manring (a driving and devastatingly gifted bassist, as his solo records and work with Sadhappy testifies) keeps any hero-glitter under a bushel of humility here. He takes a step back, becoming just one of many element in the condensate: no more dominant then Reiter’s troubled, graceful cello or Venegoni’s poised rattlebag. Cleveland lurks in the background with his chameleonic guitar (playing a skeletal pattern of notes, a swarm of bees, a steel-shack sound, or an unknown language). Masley strokes and strikes gorgeously glassy shard-notes out of his cymbalom with his bowhammers and thumb-picks.

Patterns and presences take shape out of nothingness, drift around on the edge of perception, then suddenly and deeply solidify, impressing themselves on you as if they’ve been there for years. Half-familiar fragments of music (bits of Eastern European string quartet, Chinese and Asian music, a riff from King Crimson’s The Talking Drum) reveal themselves with an enigmatic smile while they’re well on the way to becoming something new.

This is also very beautiful music: though it’s a strung-out, unsettling beauty with an element of wild, joyous fear. The exquisite Blue Mass manifests itself like light twisting through a stained-glass prism, anchored on Reiter’s perplexing, precariously emotional cello calls above which the group fashion a soft, high night-sky of singing steel sounds. Radiant Curves is all looping contrails.

On Solar Nexus, singing bass guitar and cello interweave as Masley plucks and bows his cymbalom overhead: Cleveland’s guitar flies in out of left-field over popping, sliding, shadowy bass shapes, and everything ends in glittering, mirror-surfaced screams. As a listener, you become increasingly spooked and enchanted at the presences these sounds suggest. It feels like being stalked by the Easter Island statues in a swirling fog; or like hearing the sudden ring of an unknown voice in the haunted wind that cuts through high-tension wires overhead.

This disquietude doesn’t come from conflict. These musicians don’t battle each other. The thoughtful interview they provide in the booklet, and the watchful grace they exhibit in their interaction, amply proves the opposite. But something in the music that comes out of their alliance seems to suggest a rapt, fearful awe at the size and diversity of the cosmos; and that’s not just in the astronomer’s titles which the pieces sport.

Some music changes the way you see the world, and this is a full hour’s helping. Not so much a Big Music as a small music, something retreating into the details and filaments of unconfirmed suspicions. This could be in the rhythmic imperative of the baleful four-note Pink Floyd-ian riff in The Call, worried at by the rat-scurrying strings, space-gypsy fiddling and Manring’s anxious Jaco-in-retreat fingerwork. Or it could be in the cat’s-cradle of scrapes and rockets on cello, mingling with cymbalom mantras, on Full of Stars. Here, a tangle of miscellaneous alien squawks is surrounded by collapsing glassy percussion, fractured-tree bass noises and Cleveland’s guitar-talk, finally washing up on the shores of Chinese classical music.

The most obvious Cloud Chamber ever get is on the sketchy world-funk of Dithyramb. This is like an exploded version of the fake ethnography crafted by Byrne and Eno on ‘My Life in the Bush of Ghosts’, or by Rain Tree Crow, and passes into a high, stretched-out passage of cello and bass sustain. Travelling alongside, Cleveland’s mounting guitar journeys from sketching out cirrus cloud to lovely Vini Reilly-esque pointwork. But this is a rare moment of innocence and cheer. Much more characteristic is the air-on-a-G-string improv that bedrocks Ursa Minor, setting up tensions between pluck and sustain, between the percussive cello and phased, rapping bass; between the ominous restlessness of free open passages and the querulous, demanding blue notes of the cello solo.

The final (and untitled) experiment leaves no tone resolved – winding cello, seagull distortions and an irregular, antsy wash of noise. You’re left feeling that Cloud Chamber have dismantled the scenery between us and the infinite, leaving us losing track of time, of solidity. Falling through the world. Suddenly turning around to find the whole colossal starry wonder of the universe at your back, and thrilling with a terrible flinch of delight.

Somehow Cloud Chamber are picking up on something that most of us miss: revealing something unseen by reacting to it. Hearing ‘Dark Matter’, you feel as if you’ve been allowed to watch the ambiguous wonder of something changing, and changing decisively – a presence inferred – and that you’ve been allowed to be part of it.

Science, or magic? Doesn’t matter. Live within it.

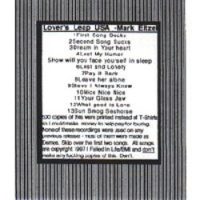

Cloud Chamber: ‘Dark Matter’

Supersaturated Records, SUPERSATURATED 001

CD/download album

Released: 11th November 1998