Compare and contrast. A while ago, Bowie – in a last-ditch attempt to prove he’s still relevant, still the musical chameleon of old – clambered aboard the drum’n’bass gravy train. That music’s normally made by lone bedsit technoheads; Bowie tried to do it with a bloated old rock band. Oops. Still, being Bowie, he could always pick up the phone and request the services of Goldie or some other jungle luminary. The end result sounded clumsy and desperate and – pointedly – as if Bowie had no real interest in drum’n’bass, since he kept dragging the music back towards the ever-more-familiar Bowierock. Not good.

On the other hand… Bill Nelson, him from ’70s Bowie contemporaries Be Bop Deluxe (and a man who mostly holed up in an ambient hermitage in Wakefield during the ’80s and ’90s) has also discovered drum’n’bass. A year before Bowie, too, with 1996’s rattlin’ good ‘After The Satellite Sings’, which sounded – unlike Bowie’s studied “so-how-do-I-do-jungle?” approach – like it had been a revelation and release to him, and without surrendering his own musical personality. Call me romantic, but I could imagine the middle-aged Nelson huddled over his radio each evening, tuning through the FM jungle pirate stations, listening in awe to the complex rhythms and then rushing to his music room to apply what he heard.

‘…Satellite…’ was a suave salvo of smartly retrofitted ’50s-accented art-pop with a bloodstream of “quintessentially English” drum’n’bass, if you can imagine such a thing – Nelson’s laid-back vocals (like a cross between David Sylvian and Cabaret Voltaire’s Stephen Mallinder) topping a very compacted sound, curiously lacking bass oomph but loaded with frenetic drum patterns, beatbox-assaulting jungle snares, burbling electronics and witty speech samples, including someone sounding suspiciously like Maggie Thatcher exclaiming “absolutely dazzled!” over the rush of beats. It was cheeky, it was damn cool, and it had a heart beating under its sharp starched creases.

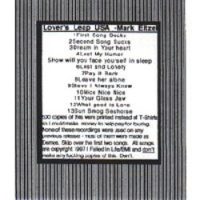

‘Atom Shop’ is the follow-up; a boxload of demos that failed to get enough funding for the full studio treatment. All the better, ‘cos we know that that way lies ‘Earthling’, Bowie lumbering into a clumsy three-point turn and spilling his load. This album’s rougher edges help – not enough to convert a hardcore junglist, but evading the slickness of most crossover efforts. And it continues ‘…Satellite…’s so-quaint-it’s-cool eccentricity, from Nelson’s memories of being in hock to American glamour during his ’50s childhood and art-college ’60s in Yorkshire.

Pulp fiction, Beat writers, cartoons, natty bebop and cars with silver fins are all part of Atom Shop’s dream fabric. It kicks off with Wild & Dizzy’s swirl of trumpet mixups, dry drum’n’bass pulse, chill synths and blue guitar, peppered with ’50s dude voices. And one of the other songs is called Viva Le Voom-Voom, baby. There’s a lot of fanboy energy here: he’s knocking on 50, but Bill Nelson still sounds naïve and sparkling with enthusiasm, bless the old goat.

Though one thing you notice pretty fast is that ‘Atom Shop’ doesn’t have the hurtling clubby drive of ‘After the Satellite Sings’. Train With Fins looks back towards the more drum’n’bassed ‘…Satellite…’ songs like Flipside – fast and clattering upfront snare drum patterns, with a techno twang and banks of horn-like guitars calling up the ghosts of Stax – but, though speedy, it never breaks much of a sweat. Which is also true of Rocket Ship’s sliding jazz/d’n’b snake rattle and Trevor Horn stabs, or Popsicle Head Trip’s Ferry smooch and tight heavy-metal riffs – all mingling through the drum’n’bass dryness, but the beats ain’t so obvious as they could’ve been.

Magic Radio has a light d’n’b push to it, but ends up like The Orb doing Somewhere Over The Rainbow. ‘Atom Shop’ sounds more touched deeply in passing by drum’n’bass, rather than grabbed by it; as if it’s freefalling away with the breakbeat imprint stamped onto the songs, a teacher’s kiss. Here you’ll more often feel the pathways of d’n’b rather than the punch; the points where space has been prepared, the dynamics of the beat, waiting for the kick that never quite comes.

Oddly, though, ‘Atom Shop’s a much blacker album than its predecessor, even if it does sound less like a session on Massive FM. ‘…Satellite…’s most awkward point – the strafing, Fripp-like guitar solos – have been phased out for a bluesier approach. Nelson’s guitar is busy everywhere, and if there’s some of B.B.D.’s fluid finickiness to it, he can also sound like a sample-era John Lee Hooker, or the subtler detailing Hendrix of Little Wing and Up From The Sky. All this is dovetailed into the minimal trip-hop feel taken to the top of the charts by Garbage, Sneaker Pimps et al (especially for the more ominous Girlfriend With Miracles), but Nelson’s got a more developed musical sense.

So everywhere you look, there are things going on: elements of electronica, samples and live instruments in a complex, but never fussy or muso, interweaving. Dobros and slides are all over Pointing At The Moon’s sleepiness, little bits of rural blues and gospel organs jostle into the arrangements; and so do probably all the “s”s in Mississippi too, if you can find ’em. And jazz dances wherever there’s room; trippy Dizzy Gillespie trumpet cascades, cheeky clarinets, even a bit of scat. Bill Nelson’s found, and gone into, the future we’re starting to guess at from our Portishead records and big-beat singles. A glittering, malleable, disorienting wonderland built out of chewed-up scraps of our past and ghosts in the record players. Something which he pins down in the sizzling hip-hop/jazz hybrid of Spinning Dizzy On the Dial when he sings “I’ve seen the luminous stuff of dreams, / I know what’s going down… Awake to all eternity / with the jazziest ghosts in town.”

It’s about a sensibility, I guess, a feeling. Which leaves us with the preoccupations of Nelson’s sighed, sometimes stoned vocals through an album of songs that are mostly poised in dreaminess. ‘…Satellite…’ celebrated the liberation Nelson’s kinetic d’n’b exploits offered him, poked fun at those who thought he might be a little old to join the jungle massive (“I had my sonic youth / When you were lost in ether… / I’ve got nothing to say, and I’m saying it. / Yeah, that’s the stuff for me.”) and had an undercurrent of suspicion at the American dream (“Whither thou goest, America, in thy shiny car in the night?”). But ‘Atom Shop’s more content to bask in sighs about “the way things swing”, “moving stars spun from mirror ball”, “Chet Baker on the lo-hi-fi”, trippy kittens, glamour girls from Mars, and Kerouac’s Dharma Bums. Perhaps he made his point the first time around.

Rest assured that it stays on the right side of Austin Powers, thanks to things like the Beat-rapping on Billy Infinity, the shuffling shoe-drag balladry and springy guitars of She Gave Me Memory, and the way in which My World Spins cooks everything together best – gospel emphasis, lucid little guitar and electric piano strums, pitter-pat drum’n’bass velocity, a Cars-style creaky hipness and Nelson’s determination to keep his head clear: “now everybody’s got their information / but none of it matches mine. / Saints preserve my reputation and keep my thoughts sublime.” The sense of a mind open to new sounds and influences pervades. Before the closing Jetsons-style supermarket jingle, Nelson’s declared himself to be “sending signals and leaving clues / from the hymns of history to the far-future blues.”

And aside from the excitement for the listener, part of the greatness of Nelson’s current trajectory is hearing a rejuvenated art-rocker enjoying exploring startlingly new musical forms and weaving them into his history. Doing it for himself, without a style guru or scenester shoving a batch of 12-inch white labels into his hands, saying “Sample some breaks from this – it’s what the kids are into.” Keep flicking through those FM stations, Mr Nelson…

(review by Col Ainsley)

Bill Nelson: ‘Atom Shop’

Discipline Global Mobile, DGM 9806 (633367980625)

CD-only album

Released: 15th September 1998

Get it from:

Best obtained second-hand.