Exchanging the Bay for Times Square seems to have lent his work an East Coast leanness. Now Eitzel’s songs exist in a flat, pressed-out space, far removed from AMC’s rich troubled orchestrations, or even from the jazz’n’torch-toned crooner feel of his ’60 Watt Silver Lining’ solo debut. Sometimes more acid is etched into a song via a bleak, distant bilous buzz or splurge of electric guitar (from former Cramp/Bad Seed Kid Congo Powers – the hollow roar of an empty belly at 4 a.m. A couple of songs are hammered home with bass and drums, courtesy of various Yo La Tengo-ists and Sonic Youth-ers. But most often it’s the man himself alone. Tumbles of bleak, dirty imagery which Eitzel’s cracked, scuffed baritone (sometimes horrified, most often seamed with the scars of painful living) releases over the tangled patterns of the acoustic guitar he fingers as if it were a crown of thorns.

Previously, in the transcendent sadness of AMC songs like Blue & Grey Shirt or Will You Find Me?, this recipe included beautiful compassionate tunes which yearned and reached towards something beyond the earthbound and betrayed. ‘Caught in a Trap…’ (which actually predates ‘West’, Eitzel’s gentler but underwhelming ’97 collaboration with Peter Buck) makes few attempts to sweeten the bitter brilliant pills of Eitzel’s words. Its songs, voiced in a spare fatal music pitched between Robert Johnson and Nick Drake, increasingly illustrate a life close to an exhausted edge.

If it isn’t quite Eitzel’s ‘Pink Moon’, it comes near enough in its cryptic fatalism – though his image of a barfly Santa Claus pursued by wolves on Xmas Lights Spin suggest it might be his Hellhound On My Trail. Eitzel’s surreal yet bitingly direct lyrics spin past in a tattered blur of clown suits, heavy air, butcher’s shops, paralysed snowmen and the inevitable cheerless bars – sort of like Jean-Paul Sartre as a battered folk singer, trapped in a junkshop haunted with the tracings of hopes and dreams.

Importantly, though, it’s not a question of self-pity. Are You the Trash addresses a hapless somebody lifted and dumped by a seductive other (“Evil wears a big smile, evil loves your mind, evil gets what it wants, evil leaves you behind…”). Yet it acknowledges our own capacity to play out our victimhood – “Even when he hurts you, well, it all seems okay. / His beauty is always beyond you / and somehow always gets in the way.” Years ago, Eitzel reminded us that “bad habits make our decisions for us.” ‘Caught In A Trap…’ deals with what happens when those habits become a way of life, as they have for the lost souls he’s sketching when he sings “most people want to inhabit their lives like ghosts and drift from room to room, / and brag about what imprisons them, and wait for the sweep of a broom.”

This time around, it’s more of a warning. On Auctioneer’s Song your heart can pull skywards like a balloon, but at the price of being as loseable, likely to find all of that lift someone else’s careless hot air, while callous smiling figures prance in to move the world on around you. Whoever’s narrating the drained Bob Mould-ish Cold Light of Day, wrapped up in ice-storm guitar, is frighteningly isolated – lurking in “the darkest part of the trees” or “five fathoms down”, determined not to hurt anybody but in constant fear of discovery. Queen of No One seems to be a portrait of a gay bar filled with scared men unable to find courage even on their own turf, as if frostbite had suddenly scarred and paralysed them at the humid peak of their Mardi Gras.

While in the past Eitzel might have railed against these little stagnations, now he’s considering them with a new eye. As prompted on the otherwise exhausted Goodbye: “Seeing eye dog on the end of its leash says ‘how can you live without trust?'” Often the best decision seems to be to close things down with as much grace and acceptance as you can. One song, with a hushed dark finger-picked melody mixing seduction with warning, sees Eitzel left behind, watching his companion travel solo on a collapsing funfair ride and concluding “If I had a gun, I would seal my fate with you… / I would give you your freedom.” Maybe it’s suicide or murder he has in mind, maybe a death pact or an escape, but you know that given the power he’s going to make some decisive gesture, simple and final.

And the need for this becomes heartbreaking in Go Away (the latest in Eitzel’s vein of harrowing songs about his doomed muse Kathleen Burns), during which Eitzel seems to be pushing with both palms and a stricken gaze, trying to tap the strength of his towering love into one last desperate attempt towards freeing his lover into an uncertain redemption: “I know you’ve got a plank to walk, I know you’ve got a kite to fly.” The knowledge that you’re going to have to strip yourself away from someone for whom you can do no more – or whom you simply hinder – is far harder than a simple thwarted love. That’s the place where everything slips out of both your grasp and your tread – as Eitzel sings “my touch just makes you draw / farther and farther / and farther away.” And it’s no wonder that the way he’s howling the title in the chorus finds him stuck on the hard place between searingly selfless compassion and blind, wounded resentment.

At least he’s seen a few ways out of the trap. On Atico 18 things have got to the point where cynicism manifests as an aimless couch-potato snake haunting the living room, but even as it grumbles in the corner, it’s lost its power. Eitzel’s already ignoring it: “the only love you’ll ever know is to look beyond the things you know.”

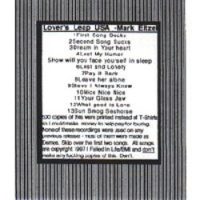

By Sun Smog Seahorse (which also made a showing on last year’s rare-as-hen’s-teeth, fans-only album ‘Lover’s Leap USA‘) he seems to have reached a point of peace. Squinting up throught the fog into a sky that finally seems benign in its indifference; screwed-up eyes and relinquishment, a rope that “ties it up, delivers it home.” It feels like a suicide abandoned – one which has been lost to a day’s acceptance. Redemption in the ability to let go, to blank out of it for long enough.

Mark Eitzel: ‘Caught in a Trap and I Can’t Back Out ‘Cause I Love You Too Much, Baby’

Matador Records Ltd., OLE 179-2 (7 44861 01792 9)

CD/LP album

Released: 20th January 1998

Get it from: on general release.

Mark Eitzel online: